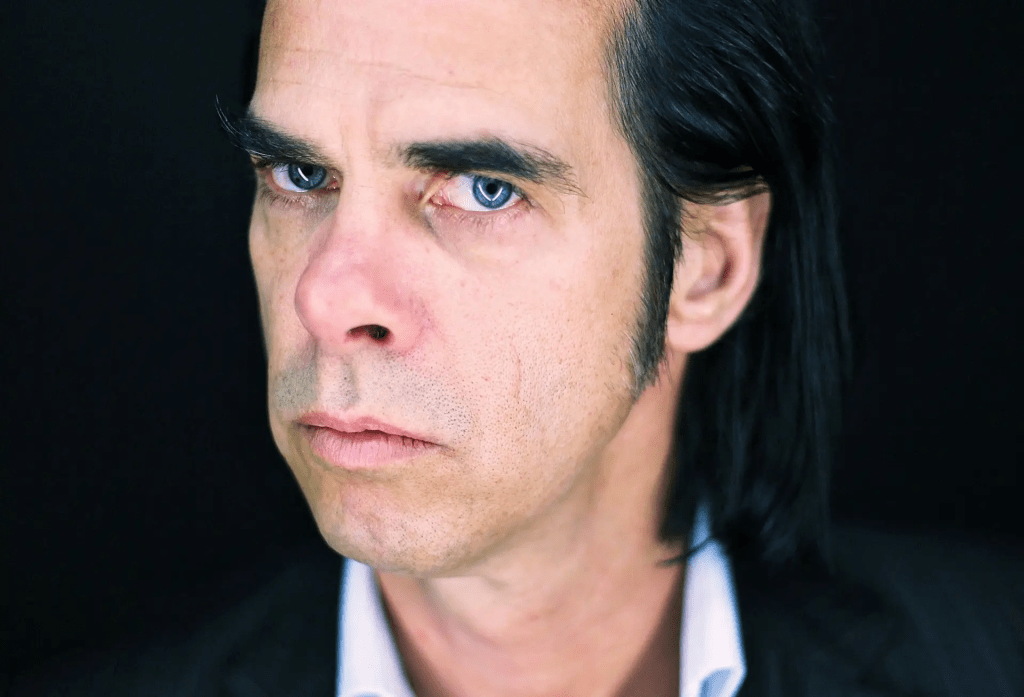

“Religion is spirituality with rigour,” Nick Cave says, half-laughing, half-serious. But beneath the quip lies a depth of insight that names something essential: that the spiritual life is not only about yearning, but about consenting to be shaped by the weight of that yearning. In a world often suspicious of structure and reverence, religion can seem like an imposition. But maybe it is a necessary one. A structure for the soul. A rhythm for those who are restless.

Augustine’s words—“our hearts are restless until they rest in you”—echo throughout this reflection. Restlessness is not an aberration, but the human condition. We are not well-adjusted creatures who occasionally experience loss; we are creatures of loss, fashioned with a longing that no finite thing can satisfy. In that sense, grief is not a club no one wants to join. It is the common thread of our humanity. And here is where religion becomes something more than therapeutic self-help or personal spirituality. It becomes a language, a form, a discipline for making sense of this condition.

To say “religion is a crutch” is not, in this light, an insult but a mercy. The image is apt. A crutch is for the wounded—and who among us is not? There is a quiet cruelty in those who mock faith as weakness, as though needing help were a flaw rather than the defining mark of being human. In fact, what’s brittle is not religion, but the rationalistic insistence that we are self-sufficient. Western culture, so allergic to weakness, builds its towers on denial. But when the ground shakes—when a pandemic strips away illusion, or a loved one disappears into absence—then the thinness of our constructs becomes clear.

Religion does not necessarily “fix” this, and nor should it. But it does something better: it befriends reality. It gives us forms for facing what is—our yearning, our fragility, our loss. And yes, sometimes our joy. That befriending may look like liturgy, with its deep rhythms and cadences. It may sound like hymns sung in a beautiful old church, where music stirs memory and the veil thins. It may be the communion table, where even an atheist can weep and not know why. It may simply be the decision to sit with mystery instead of running from it.

Religion, at its best, is not a defensive clutching at certainty but a practiced humility before the incomprehensible. Its doctrines, rituals, and traditions are not answers in themselves but containers—vessels for the lived experience of loss and love, of hope and ache. Religion asks something of us: not merely to feel, but to be formed. Not only to long for transcendence, but to consent to a path that teaches us how to live with that longing faithfully.

Yes, spirituality can flicker in moments of awe, in grief-stricken clarity, in spontaneous kindness. But it can also dissipate like morning mist. Religion, for all its flaws and failures, insists that we keep showing up. That we rehearse our convictions in word and action. That we become the kind of people who can carry grief and hope in the same body.

And maybe that’s why, even in our most skeptical moments, we still walk through the church doors. Not to draw closer to reason. But to enter, however falteringly, into that other dimension—where absence and presence mingle, where beauty steadies the heart, where love remembers the lost and calls us forward. Because in the end, the real scandal is not that religion is a crutch. It’s that we are limping, and still pretending otherwise.

Based on Nick Cave – Loss, Yearning, Transcendence, 22 November 2023

https://onbeing.org/programs/nick-cave-loss-yearning-transcendence/

Leave a comment